"Upskilling" is a popular phrase, used liberally by educators, vendor trainers and other organizations like Microsoft (Global Skills Initiative) and LinkedIn (Skills Path) with their own programs of numerous courses covering many aspects of IT. This sounds a great idea for bolstering IT skills for the changing world of computing.

I have my reservations though, based on 50+ years of IT experience, both at the coal face across a wide set of industries and latterly as author and researcher. I have examined many, many computing curricula across schools, universities and other organizations offering various forms of "IT" education and, like Sir Thomas Beecham, I have "formed a very poor opinion of it." Why?

What is the Problem?

That is difficult to put into a few sentences as there are many aspects of this current computing education which make me uncomfortable.

■ One is the lack of a common idea of what constitutes IT or "digital" knowledge, from Mrs. Jones using the internet for supermarket shopping to people at the forefront of technology.

■ The variation in topic coverage, going from the nitty gritty to the sublime in the same course but for different topics — it feels bitty and cobbled together, possibly developed by a lot of people working separately.

■ The lack of pragmatic content, particularly in computer science (CS) courses, for example, "... this technique is used in the X industry to estimate the depth of a depletion layer in semi-conductors and also in Y industry" never appears. In other words, it lacks real world context.

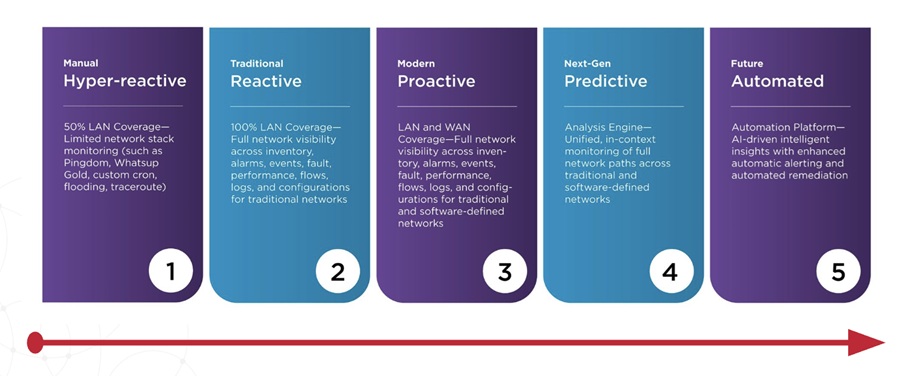

Let me give an illustrative example. In network courses or modules, one is taken on a journey through the bowels of networks — routers, MAC, 7-layer models, TCP/IP and much more. There is no discussion of what the pragmatic aspects of networks are — congestion, compression, data loss, high availability, cybersecurity forensics, network performance management, network simulation tools — and a host of other day-to-day aspects of designing and running a network. In short, much of the computer teaching fails to answer the "so what?" question.

■ There is a plethora of courses offering a specialism at the end of it and cybersecurity is a case in question. I have looked at many of these and none, apart from a single IBM course, ask for any previous training (prerequisites). This attempt to develop a specialist from a standing start is akin to trying to become a cardiac or brain specialist without going through general medical school.

■ The overall impression I was left with was that most courses resembled a fairly random set of specific topics with no feeling a synergy and what IT was all about overall. This left me with the impression that I might do all the topics in a course but still feel uneasy about whether I could give a one-hour presentation on what IT was all about.

I have two analogies which might illustrate what I have said above more clearly.

A nautical analogy. I join a course on sailing and am trained on yachts, speedboats and a few larger vessels and graduate feeling very pleased with myself. However, I meet an old salt who had sailed the seas for decades and he asked me what I'd been taught about navigation — with instruments or by the stars — and about trade winds, dangerous waters, different ports and assessing weather conditions in the absence of a forecast. I pleaded a headache and politely bid him farewell and a fair wind on the seas of life.

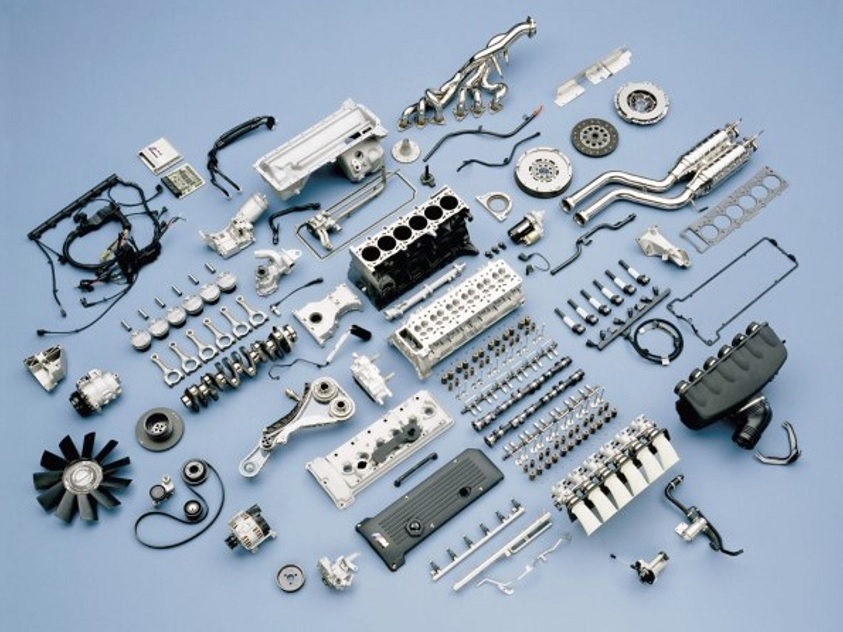

Picture a hypothetical course on the motor car which I undertook. It covers the components parts — engine, brakes, transmission etc. — dealing with equations of coefficients of friction, the Carnot Cycle, adiabatic expansion of gases, hydraulic transmission and a host of other topics. Great!

Figure 1: Parts of an Automobile Engine

Figure 1: Parts of an Automobile Engine

However, when I re-joined the real world after three year's study, I realized I couldn't drive a car, read a map, plan a journey, assess what kind of vehicle I needed for my purposes, had little idea of service intervals and other day-to-day things necessary in possessing a car.

Need I go further???

What Is the/a Solution?

I have thought long and hard about this and came to the conclusion that all IT education should fit into a framework and what takes place within it reflect the activity flow of nearly all IT projects, large and small. When people understand this, they see the value in taking this view from 10,000 feet and then home in on topics, rather like one does with views in Google Earth. It is also key that people recognize that they are moving into IT as a career and not just a job paying X £ or $.

A key factor which tells why the career mentality is superior to the job mindset is the volatility of change in IT. Many people have written about this and point to the idea that IT jobs, like the Covid virus, mutate over time until its boundaries change or, in the worst case, become a different subject or, worse still, become obsolete. The half-life of an IT job in a particular form is estimated to about 18-24 months, hence the need for rapidly changeable training.

Summary

■ The field of education is like a patchwork quilt of difference shades and depths and often comprises a set of topics with little connectivity or "where used" context. It is also limited in scope and ignores major topics such as mainframes, enterprise computing, cloud, service levels and high performance computing (HPC). These omissions limit the students' career scope considerably.

■ Much IT education is based on computer science (CS) which is very limited in its scope and rarely offers workplace context.

■ There is a prevailing idea that an IT specialization can be taught from scratch without solid prerequisite knowledge.

■ There is also the mistaken notion that "coding and algorithms" are the "be all and end all" of IT work. This activity is just one in a chain of activities.

■ An IT project is a chain of activities which depend on each other for the success of the project.

■ There is a need for a broad underpinning IT education track as a springboard to promotion or specialization.